Memoirs of a Boffin

Chapter 13: The Club of Rome

The studies sponsored by the OECD Committee on Science and Technology Policy, during the years in which I was a Member, provided all the Members with data on the conduct of research and development in all the member countries and in some others, such as the Soviet Union. Indeed we were inundated with data which included both past performance and projections for the future, which, like most growth projections in my experience predicted exponential increase for the foreseeable future. I remember curves showing the projected increase in the number of scientists and engineers. My old friend and wartime colleague Vivian Bowden (now Lord Bowden), in a keynote address to an OECD seminar on Science and Public Policy, ridiculed such simplistic projections and the absurdity of planning on the basis of prolonged exponential growth. He was heard to remark that an extrapolation of the figures would show that every man, woman, child and domestic animal would eventually be engaged in R & D.

There was already concern in many quarters about the growth of the world population beyond the point where there were enough materials, food and energy to support it. There were serious discussions about the depletion of material, food and energy reserves and the economic, logistic and political difficulties of distributing them fairly. There were discussions about the rapid deterioration of the environment – air, water and land – because increased consumption meant discarding more waste into the environment. There was an increasing realization that one day very soon countries were going to have to plan for the flattening off of the growth curves in spite of the potentially painful consequences. It was quite obvious that the exponential increase of world population would come to an end within the next century, one way or another. The Earth is finite. It has only a certain limited capacity. Growth can only occur over a very limited period, until that capacity is exceeded. It needs a great deal of advance planning over many years to effect the transition smoothly from growth to the steady state. But politicians rarely think in those terms. They think growth is forever because, for most of them forever is the time until the next election.

In the view of many of us, even in the 1960s, we were already passing the level of world population that could conceivably be sustained even if, by some miracle, all politicians in the world could be persuaded to work cooperatively and rationally towards that end. The process should have been started years before. Now, in the 1960s, it was desperately urgent. Existing international organizations were too bureaucratic and obviously too slow to achieve anything in time. So thoughts turned to the possibility of analyzing these global problems and developing solutions in informal, non-governmental groups.

The intensive work with the Science Policy Committees of the international organizations (OECD, NATO and the Commonwealth) in the period 1965 to 1975 had put me in the right place at the right time to be around at the birth of several exciting non-governmental international initiatives. The first and most important of these was the establishment of the Club of Rome. I first heard about it from Dr. Alexander King in the late 1960s.

At the time, Alexander King, a distinguished English research chemist, was Director General of Education and Science at OECD. In that capacity he organized the meetings of the OECD Committee on Science and Technology Policy. As Canadian Member and also, for a time, Vice-Chairman of the Committee, I had to work very closely with Alex King as well as with the other members of the Committee Executive on my frequent trips to Paris.

Towards the end of 1966, Dr. King came across a speech given somewhere in South America by an Italian called Aurelio Peccei, who at that time was unknown to King. The general theme of the speech was the same as that of a series of lectures Peccei had been giving on “The Challenge of the ’70s for the World today”. He was concerned about the effects of galloping population growth, the consequent rise in consumption of food, materials and energy, leading to depletion, shortages and, at the same time, environmental degradation. He was also concerned about the disparity between the North and South. He emphasized that it was essential for the NATO and Warsaw Pact countries to collaborate before real efforts could be made to attack these global problems.

The contents of the report on Peccei’s speech so closely coincided with King’s own concerns about the future that he wrote to Peccei suggesting that they meet the next time he was in Paris. The meeting took place and turned out to be not only a meeting of men, but of minds. Both men recognized that, in order to create the conditions for the survival of civilized life on Earth, politicians and world leaders must be provided with the ammunition for making courageous, difficult and even unpopular policy decisions. They would have to make commitments for the long-term future, far beyond their individual terms of office. Peccei and King agreed that, none of the formal intergovernmental international organizations such as the UN could do this – at least not in time. These bodies were far too cumbersome. It was characteristic of both men that they immediately got down to business. They discussed how they could assemble others who were similarly concerned about the world future in a group that was independent of race, politics, religions and bureaucracies.

Both Peccei and King had extensive international contacts, but they had very different backgrounds:

Alex King was born in England in the first decade of the century. Already a distinguished research chemist, he became a pioneer of science in government policy in Britain during the war, as secretary of the very first science policy committee at the heart of any government (he was Secretary of the Defence Science Policy Committee of the British Cabinet – the Tizard Committee). Like me, he spent the last year or so of the war with the British Mission in Washington DC, albeit at a more senior level. I did not know him at that time. After the war he introduced science policy into the newly-formed EDC, the forerunner of OECD and remained until his retirement from OECD in 1976. He moved to Paris in the 1950s and lived there, on the rue de Grenelle, for nearly 40 years. By the time he met Peccei, he was well-known and greatly respected by the leading scientists and science ministers of the OECD countries who visited him and participated in his committees.

In contrast, Aurelio Peccei was an Italian industrialist. A graduate in economics from the University of Turin, he joined the Fiat Company in about 1930. Although under continual suspicion as an anti-fascist in the 1930s, a successful mission for Fiat in China established his position in Fiat management, albeit as a bit of a maverick. It was his unconventional approach and the trust of successive heads of Fiat that gave him a considerable amount of freedom while still in Fiat employ. Peccei’s work with the anti-fascist underground during the war caught up with him in 1944, when he was arrested, imprisoned, tortured, came within an ace of execution and escaped to lie in hiding until the liberation.

Alexander King |

Aurelio Peccei |

After the war, Peccei established a Fiat organization in Latin America and negotiated an agreement with the Soviet Union to produce the first Fiat-designed cars there in a huge factory. It was on this project that he worked with Djerman Gvishiani, Kosygin’s son-in-law and Vice-Chairman of the State Committee on Science and Technology of the USSR . Gvishiani was to play a leading role in some of Peccei’s future plans (and, as a result, become a friend and colleague of mine).

While still associated with Fiat, Aurelio Peccei became President of a large consulting organization, Italconsult. He was also an executive of Olivetti and was a founder of and an active participant in the Atlantic Development Group for Latin America (ADELA). He still found time to speak all over the world about his concerns for the global future. It was while he was involved in all these activities that I first met him in Paris through Alex King.

A young Italian biographer of Peccei, Gunter Pauli writes:

“In the late 1950s, Aurelio Peccei began to consider whether he had been doing enough with his life. He had many rich and rewarding experiences; he had raised a beautiful family and had provided well for its future; he had held important positions of responsibility for many years and had learned to recognize problems and opportunities quickly and how to organize people in order to achieve goals. He was accustomed to being a leader. However, he had become troubled by the world situation and the realization that the difficulties of both the industrialized and the poorer regions of the world were mounting into a tide. He had reached what is known as “the fifth age”, that period of life when people become more introspective. However, because he was, by profession, a manager, he could not conceive of meditation divorced from action. For him, mere ideas, however worthy were not enough.”

Crusader for the Future. Gunter Pauli; Pergamon Press, 1987

That was the spirit in which Aurelio Peccei met Alex King in Paris towards the end of the year 1966. Following that meeting, the two men invited about forty of their international friends and colleagues to an informal meeting in the Academia de Lincei in Rome on the 6-7 April, 1967. The meeting was sponsored by the Agnelli Foundation. (The Agnellis were the major shareholders of Fiat.) At that meeting it was decided to give the group a name. “Club of Rome” was an obvious choice, in acknowledgement of the location of that first meeting. Peccei often quipped that it was not to be confused with “the other club of Rome – the one in the Vatican”.

The Director of the Batelle Research Institute in Geneva, Hugo Thiemann, offered to provide facilities for regular meetings of the Club. Hugo was also a member of the OECD Committee on Science and Technology Policy, of which Alex was Secretary, and later became one of the two Vice-Chairmen at a time when I was the other.

Members of the group that had met in Rome met several times in Geneva during 1987-88 to hold discussions. At that time the Club had an informal “inner group” of six but had no corporate existence. The inner group consisted of:

- Aurelio Peccei

- Alexander King

- Hugo Thiemann: Director, Batelle Institute, Geneva

- Max Konstamm: A German Professor

- Jean Saint-Geours: Ministry of Finance, Paris

- Erich Jantsch: Author of “Technological Forecasting”

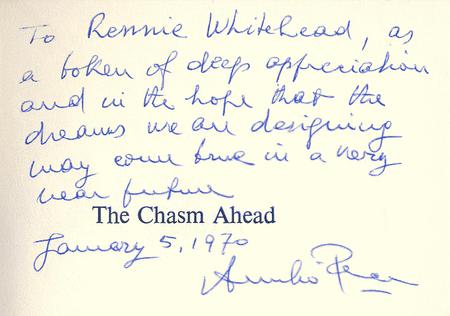

Aurelio was still addressing groups in various parts of the world and had put some notes on paper for these lectures. He expanded these into a book, The Chasm Ahead [1] in 1968. In the book he described the global problems that he saw as so threatening. He decided to spend the greater part of his time and money in calling attention to them and pressing for government action throughout the world. He did so until the time of his death in 1984. His instrument was “The Club of Rome”.

In 1954, Dr. Harrison Brown of the USA had written a book, The Challenge of Man’s Future [2], in which he outlined, with great clarity and foresight, most of the major problems that, fifteen years later, became the preoccupation of the Club of Rome and which now, forty-odd years later, seem to be even further away from solution. Even today, Harrison Brown’s book is still one of the best analytical presentations of the probable consequences of population growth and the inevitable shift from fossil fuels to other sources of energy. Yet, at the time it was written, no-one was apparently able to focus the attention of governments or the public on these topics. The book was excellent – endorsed by no less a figure than Albert Einstein – but it apparently had little impact, presumably because it was perceived as being before its time. Harrison Brown was later Foreign Secretary of the USA Academy of Sciences. His name reappears later when, in the ’70s, he and I and served together on the Council of another non-governmental organization, IIASA, that was created as a result of Peccei’s efforts.

Peccei’s appeal, in The Chasm Ahead was, unlike that of Harrison Brown, highly emotional and was made with the express intention of influencing governments to take timely action. Nevertheless he recognized the extreme reluctance, even impotence of political leaders in all countries to face problems that were beyond their political purview both in time-scale, interdependence and jurisdiction. He emphasized once more the importance of transatlantic and east-west cooperation in the approach to global problems that, in his view, should transcend national interests. He also recognized that the rate of increase of the occurrence of disruptive events was overtaking, indeed overwhelming man’s ability to cope with them – a fact that has been amply substantiated in recent years.

Since The Chasm Ahead was published, in 1968, many of the problems to which he drew attention have been the subject of features on radio and TV and in the press – thanks largely to the Club of Rome. But at the time of Peccei’s initiative there was comparatively little public knowledge or concern about the future.

1. The Chasm Ahead. Aurelio Peccei; Macmillan, 1968.

2. The Challenge of Man’s Future. Harrison Brown; Viking, 1954.

I first met Aurelio Peccei in Paris in about 1968. He was introduced to me by Alex King. I saw a big gentle man of military bearing with a mane of grey hair, bright blue eyes and lines of suffering and compassion on his ruggedly handsome face. In his characteristic way, he immediately began to discuss what Canada could do to further the objectives of the Club. These discussions led to a close friendship between us for many years and a strong participation by Canadians in the Club of Rome.

At this time Peccei was becoming increasingly impatient that the early meetings of the Club had discussed the problems at length but had not developed any course of action. What he was seeking was an effective methodology to tackle the issues of what he termed the “problematique”, which he described in The Chasm Ahead as “a tidal wave of global problems”. To this end he sought the views of a well-known American systems analyst, Professor Hasan Ozbekhan, on the development of the first “problematique” of the Club of Rome.

Ozbekhan became interested and he and Erich Jantsch made a presentation of the problematique at the European Summer University in Alpbach, Austria. Eduard Pestel, a professor from Hannover, was at that meeting and expressed his interest in the Club to Peccei. By the end of the year, Pestel was not only a Member of the Club but had become a member of the Executive group of six. He was to play a major role in the Club right up to the time of his death in 1988. It was at this meeting that Peccei decided to co-opt Ozbekhan as a consultant to develop the “problematique”.

Ozbekhan was to make his initial report to a meeting of the inner group (the “Executive”) of the Club of Rome in December, 1969. I was not yet a Member of the Club – not because of the lack of an invitation, but because I felt that, in my sensitive position in the Privy Council Office, it might be seen as risking conflict of interest. Also, my wartime experience as a boffin – a backroom boy – never wore off and I have always been more comfortable and more effective as a catalyst causing things to happen by working behind the scenes. Nevertheless, Aurelio Peccei invited me as an observer to that executive meeting, which was held in the Palais Pallavicini, opposite the Hofberg Palace in Vienna. In addition to Hasan Ozbekhan, who was making his presentation, there were two other non-members present. They were Djerman Gvishiani, the Vice-Chairman of the Soviet State Committee on Science and Technology, whom Peccei knew and liked from his Soviet-Fiat negotiations and Thor Kristensen, the Secretary General of OECD.

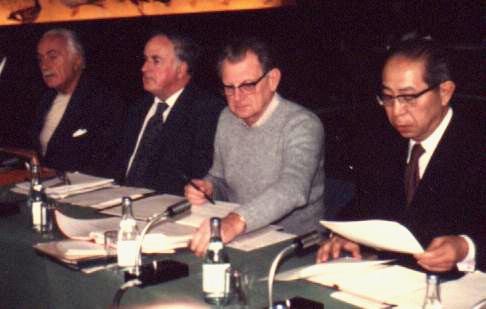

An indistinct but precious picture of my good

friends (L to R) Peccei, King, Thiemann and Okita.

Taken at an early meeting of The Club of Rome

The executive “inner group” itself had changed by then. It still included Peccei, King, Thiemann and Jantsch, but Max Konstamm and Jean Saint-Geours had been replaced by Professor Eduard Pestel of Hannover and Saburo Okita of Japan. Pestel was a member of the Board of the Volkswagen Foundation and a colleague of mine on the NATO Science Committee in Brussels. He later became Minister of Science and Education of Lower Saxony. Sabuo Okita was a leading economist and later Foreign Minister of Japan. At the time, Okita was also Chairman of the OECD Committee on Science and Technology Policy, in Paris, of which Alex King was Executive Secretary and Hugo Thiemann and I were Vice-Chairmen.

The meeting in Vienna had two objectives. One was to give the Club of Rome legal status by incorporating it as a non-profit organization; the other was to define the problematique, with the help of Hasan Ozbekhan. The first objective was met; the second caused some trouble, for part of which I may have been to blame.

During Ozbekhan’s presentation at the meeting in the Palais Pallavicini, I became increasingly puzzled as to what was its purpose. It was couched in the most intricate language – what I, as a scientist, call disparagingly “social science jargon”. I think that is because, while scientists invent new words for new concepts (like ‘transponder’, for example), social scientists often seem to redefine existing words, which tends to confuse the reader.

The meeting did not adopt Ozbekhan’s statement of the problematique, because Pestel and Thiemann particularly among the Members hedged a bit and I am sure Gvishiani and I showed our doubts, even though we were only there as observers. I don’t think that Alex King commented adversely, probably because he knew this project was dear to Peccei’s heart and Alex knew Aurelio’s sensitivities better than any of us.

After the meeting Aurelio asked me what I thought about it. I hesitated a bit, feeling, as an observer, that it was not really my place to comment. Nevertheless, with his encouragement, I finally told him that, learned as Ozbekhan’s work no doubt was, it was not likely to be comprehensible to either the public or to politicians to whom the Club of Rome message was to be addressed. That really put the cat among the pigeons. Aurelio became very upset – in fact at one point he was actually in tears – and it took Alex and me a couple of hours over dinner to pacify him by suggesting (without a lot of confidence on my part) that he ask Ozbekhan to have another crack at the job. I really felt that in spite of the fact that Ozbekhan had a lot to offer through his academic work, his style did not match Peccei’s vision at that point.

As a consequence of the meeting, the Club of Rome was incorporated in January 1970 as a non-profit organization under the laws of Switzerland, with its siège sociale at the Batelle Institute in Geneva.

That was my first visit to Vienna, a city which I later visited often and came to love. I explored the Kärtnerstrasse and the Graben and climbed the tower of St Stephen’s Cathedral (I was staying at the Stephanplatz Hotel close by). I went to the Opera, the Sunday morning rehearsal at the Lippizaner riding school and the marvellous service in the Hofburg Musikapelle.

The day of the meeting, we were invited to lunch by the Chancellor of Austria. I found myself seated next to Kurt Waldheim who had lived in Ottawa for several years as Austrian Ambassador. He was the Foreign Minister of Austria at the time. We found we had many mutual friends, particularly George Davidson who was Secretary of the Treasury Board for many years, and conversation flowed easily. I found him very sensitive and sympathetic to the concerns of the Club of Rome. We had no hint at that time of the scandal that was to engulf him in later years.

That evening we were invited to Gvishiani’s suite in the Imperial Hotel in Vienna. He served his favourite fruit vodka. I asked him how to make it; this is what he said: “Fill a large pitcher with whole fruit, for example peaches, apples and plums. Do not remove the skins. Fill the remaining space between the fruit with vodka and refrigerate for at least a day. Then drink it. Later, eat the fruit”. That party was a unique experience and the beginning of a long warm relationship with Gvishiani which blossomed in the 70s when we worked together on the Council of IIASA. But that comes later.

Aurelio Peccei had first come to Canada in June 1969 with Alex King. On his next visit, not long after the meeting in Vienna, he brought me a copy of his book The Chasm Ahead, inscribed with the words: To Rennie Whitehead, as a token of deep appreciation and in the hope that the dreams we are designing may come true in a very near future, January 5, 1970. Aurelio Peccei.

On this occasion he came to dinner at our home. and talked a good deal to our 14-year old son, Michael. Several months later, when I mentioned Aurelio Peccei’s name at the dinner table, Michael asked, “Is that the Italian who came to dinner a few months ago?” I replied, “Yes – do you remember him?” Michael said, “Yes, I do; I knew he was a great man before he even opened his mouth” – an unsolicited testimonial to Peccei’s charisma!On the occasion of that visit, we had arranged a small dinner meeting with Prime Minister Trudeau. Trudeau already shared some of Peccei’s concerns about the future and he was sympathetic to the aims of the Club. We also had lunch at Rideau Hall (the residence of the Governor-General Roly Michener). At dinner at 12 Sussex Drive (the Prime Minister’s residence) I found myself seated next to Jean Chrétien who was then early in his long run of Ministerial appointments in the Trudeau Cabinet. I remember that his attractive boyish manner, sharp intelligence and good humour impressed me very favourably at the time. I have never had occasion to change that impression.

After dinner, Trudeau arranged a circle of chairs in the drawing room and led a prolonged discussion of the problems perceived by Peccei and the role of a Club of Rome. The group included: Michael Pitfield, Marc Lalonde, the Prime Minister’s Principal Secretary at the time, who later became Minister of Finance; Senator Lamontagne, who created the Senate Committee on Science Policy; Pierre Gendron, the President of the Pulp and Paper Research Association in Montreal; and, of course, Jean Chrétien.

It was on this occasion that Peccei told Trudeau of my reluctance to accept membership in the Club because of possible conflict of interest. Trudeau pooh-poohed the idea and said that I could accept membership, which could be regarded as compatible with my responsibilities in the Privy Council Office. I was also to keep in touch concerning ways in which the Canadian Government could help the Club. So I became a Member of the Club of Rome in January, 1970, about a month after it was incorporated.

It was as a result of these meetings that we were able in the next few years to sponsor certain Club of Rome projects, host a meeting of the Club and establish one of the first National Associations for the Club of Rome.

In the meantime, the Club of Rome held its first formal Annual Meeting in Bern, Switzerland in June 1970. Ozbekhan was to present his revised problematique to that meeting. It did not catch the imagination of the Members. Some were reported as saying that it was too humanistic and not structured enough. Peccei was almost at his wits’ end when, towards the end of the day Professor Jay Forrester of MIT made a concrete proposal. He had previously had discussions with Peccei at MIT and he was becoming increasingly convinced that the techniques of “Industrial Dynamics” which they were successfully applying to complex industrial problems, could be adapted to model the dynamics of the world. To this end he renamed it “Systems Dynamics” at the suggestion of Eduard Pestel, who agreed to present the proposal to the Volkswagen Foundation for funding. In return, Forrester invited the six Club of Rome executives to Cambridge Massachusetts to discuss with him the parameters of the model.

The rest is history. A 28 year-old researcher, Dennis Meadows, was put in charge of the project. The Club of Rome was invited to hold its second annual gathering in Canada in April 1971. It took place in Montebello, on the North bank of the Ottawa river between Ottawa and Montreal. My wife and I felt that the warm, hospitable Country Club environment was ideal for the meeting. And so it proved. Dennis Meadows presented his plan to us at that meeting and gave a progress report. It was generally well received. A few months later, in the spring of 1972, the book Limits to Growth [3] was published. The style and clarity of the presentation of the material in the book was largely due to the outstanding work of Dennis Meadows’ wife, Donnella.

The Limits to Growth was based on the Systems Dynamics model of a homogeneous world. It took into account the interaction between population density, resources of food, energy, materials and capital, environmental degradation, land use and so on. A number of scenarios were developed in it, using computer simulation and based on the development of several hypothetical “stabilizing” policies. The results were always similar: a catastrophic fall in world population and standard of living, within 50 to 100 years if current trends continued.

The fact that Limits to Growth considered the world as a whole, without any separate treatment of different regions or countries made the model deliberately simplistic, but this over-simplification was necessary in order to have a model at all in a reasonable time. Because the MIT approach was (albeit necessarily) so simplistic it was widely criticized at the time by some academics. John Maddox, the Editor of “Nature” and Prof. Chris Freeman of the Science Policy Group of the University of Sussex led the criticism that Limits to Growth was “unscientific”. Maddox wrote a book on the subject entitled The Doomsday Syndrome [4] which was heavily critical of Limits to Growth and quite erroneously perceived it as carrying a “doomsday” message. In fact the study only projected a few possible scenarios of what was likely to happen if we did not change our ways on a global scale. It was not a forecasting document.

What the critics failed to see was that, unscientific or not, this was precisely the blunt instrument that was necessary to get world attention. Ironically enough, although Limits to Growth was only one of a number of projects sponsored at the time by the Club of Rome, it was the one most closely identified with the Club in the public eye. Consequently, instead of being congratulated for sponsoring such a novel, independent study, the Club was criticized at the time for the limitations of the Meadows’ approach and its alleged “doomsday” message. Yet earlier, less flamboyant studies than Limits to Growth had gone largely unnoticed. While Limits to Growth only sold tens of thousands in America, it sold millions in more congested countries, such as the Netherlands and Japan. It was produced in several languages.

By the early 1970s, Aurelio Peccei’s initiative had snowballed. Since those early days the Club of Rome has held full meetings almost every year, often financed by the government of the host country, and as widely dispersed as Japan, Venezuela, Germany, Yugoslavia and the Middle East. The results of studies it has catalyzed and sponsored have been published in the many books that have appeared under the sponsorship of the Club of Rome.

3. The Limits to Growth. Meadows; Universe Books, 1972.

4. The Doomsday Syndrome. John Maddox; McGraw Hill, 1972.

Over the years I attended Club of Rome meetings in several countries. One of the most fascinating was the meeting in Japan in October, 1973. I flew to Vancouver to join a Japan Air Lines flight via Anchorage to Tokyo. I was comfortably seated in First Class early in the boarding process when I felt a hand on my shoulder. It was Jean-Luc Pépin, the Minister I had accompanied to Moscow in 1971. He had left politics by this time and was concerned with some commercial undertaking. He said good-humouredly “some people have it good” and vanished en route to the economy section.

A Japanese man was seated beside me and, eventually, we got into conversation. He told me that he was representing his Company in Canada, where he and his wife had been living for some time. He was making one of his infrequent visits back to headquarters on this flight. I asked him whether his wife liked living in Canada and whether she missed Japan. He said, “Are you kidding? – She never had it so good.” He went on to explain that Japanese wives are, by tradition subservient to their husbands and she was greatly enjoying her emancipation of behaving like all the other wives in Canada. He was not sure that he was.

Later in the visit, I met an American who had married a Japanese wife and settled in Tokyo about a dozen years before. I asked him if he missed the United States. He said, “Are you kidding? – I never had it so good.” He went on to explain that he had a beautiful Japanese wife who brought his slippers and waited on his every need, while he could live like a Japanese husband, with all the independence that implied.

The Club of Rome meeting was held in the Imperial Hotel. It was a great success because it attracted about 300 distinguished Japanese invitees who participated keenly. Like Canada, they formed a National Association for the Club of Rome and initiated several modelling projects of Japan in the global environment.

The Japanese Government threw us a superb party in the Imperial Hotel Ballroom. This was my first experience of the Geishas. Beautifully turned out in their picturesque traditional costumes, they were present in numbers at the party. Tables were loaded with Japanese delicacies to eat with the drinks. It was impossible to do anything oneself. As soon as I made a move to pick up a cup and saucer for tea, one of them tore it out of my hand, another poured the tea, the first put in sugar and a third stirred it. Then I made a move towards the lobster tails but was neatly intercepted. Two of the Geishas procured a plate and neatly shelled the tails, presenting me with the meat on a plate, ready to eat. And so on. It was then I discovered what the American I had met earlier meant about life in Japan.

The projects the Club has espoused and sponsored for publication give us an insight into the way Peccei’s thinking progressed. A good deal of the early emphasis was on computer-aided modelling and analysis of the global system. The simple Limits to Growth model was followed by a series of ‘layered’ and regionalized computer models which culminated in the Pestel-Mesarovic book Mankind at the Turning-Point [5]. There was an increasing recognition of the complexity of decision analysis and the confusing role that was played by the interaction and interdependence of many of the components of the global system. There was a growing appreciation of the dangers of major decisions that were based on a grossly inadequate understanding of the workings of national and global systems.

At the same time leading world experts in food, materials and energy were consulted in a project entitled Beyond the Age of Waste. I was able to arrange financial support for this project from the Canadian Government. The impact of this important project was diluted in North America because of the extraordinary delay in the publication of the English edition of the book. A somewhat similar, but more extensive activity, led to the publication of Goals for Mankind [6], which dealt not with material conservation but with the objectives of nations, groups and individuals.

Both this project and the slightly earlier Reshaping the International Order [7] were inevitably controversial because they were perceived by some as crossing the fine line between human and political goals. Yet Peccei had seen to it that the Club of Rome membership represented all possible political beliefs from communist through liberal to the extreme right so that the Club itself could never be accused of taking or supporting any particular political or, for that matter, religious stance.

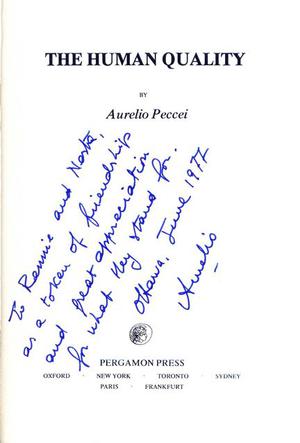

It was during the 70s that Aurelio Peccei’s attention turned from the scenarios that illustrated the consequences of population growth, materials, energy and food shortages, towards the limitations of human beings themselves. His book The Human Quality [8] focuses his concern for human irresponsibility and his undying faith that “the human quality” can be changed for the better, if human beings set their sights on it. It is in the first chapter of that book that we find the all-too-brief, reluctant autobiography of Peccei. It is typical of his modesty to condense his super-human achievements into 14 brief pages. This is a very special book to me, not only because of the inscription on the title page.

A project on learning was also stimulated by Peccei’s new direction of thought; like many others it was conducted by an independent multi-national research team. It resulted in a book, No Limits to Learning [9]. It examines the thesis that human beings have much greater capabilities for understanding and handling complexity than they usually demonstrate by their actions.

While the projects of the late 1970s mainly concentrated on the growing realization that the weakest component in the global system was man himself, Peccei did not ignore the continuing impact of technological change. A major project on micro-electronics was completed in 1981 with the publication of the book Microelectronics and Society: For Better or for Worse [10], which analyzed the impact on society of the micro-computer revolution.

5. Mankind at the Turning-Point, by Pestel and Mesarovic; Dutton, 1974

6. Goals for Mankind, by Ervin Laszlo et al; Dutton, 1977

7. Reshaping the International Order, by Jan Tinbergen, E.P. Dutton and Co Inc. NY (1976)

8. The Human Quality, by Aurelio Peccei; Pergamon Press, 1977

9. No Limits to Learning, by Botkin, Elmandra and Malitz; Pergamon Press (1979)

10. Microelectronics and the Society - For Better or Worse, by Schaff and Friedrichs. Pergamon Press (1982)

Aurelio Peccei’s perspective on the future is to be found compressed into another book, One Hundred Pages on the Future, which was published only three years before his death on 14th March, 1984. Towards the end of it he writes:

“It is evident that our current ways of thinking reflect ideologies and experiences of a past very different from the present. A wide gap has thus opened between the beliefs, values, principles, norms, frames of reference and mental attitudes that we normally employ as guides , and those that are now necessary in view of the nature and extent of the challenges of our age. This is a grave handicap, indeed.”

One Hundred Pages on the Future - Reflections of the President of the Club of Rome. Pergamon Press, 1981

It is now quite clear, many years later, that Aurelio Peccei had once again recognized the crux of the global problem well ahead of others. Only now, in the nineties, is there a dawning recognition, in a few places, that values, attitudes and, indeed, the Western way of life must change if there is to be any possibility of survival in the light of population growth and the technological environmental and political changes that have already taken place in the world.

The projects that were stimulated by Peccei and his colleagues and published as “Reports to the Club of Rome” were all performed by independent groups. The work was financed directly from conventional sources including governments, industry and foundations. Peccei insisted that the Club of Rome handle no money, nor have any paid employees. For years he handled the secretariat work himself with such informal help as was available to him at the time.

The role of the Club of Rome in these projects was catalytic: It provided the climate in which new ideas were generated; it catalyzed the meeting of researchers with common interests from different countries; it sought out interested funding agencies and helped negotiate funds for the newly-conceived projects; and it provided a forum for discussion and reports on progress. It was by adherence to this brilliantly simple “non-organization” concept that Aurelio Peccei and Alexander King established and maintained the independence and the stature of the Club of Rome.

Beyond the meetings of the Club of Rome itself, and the projects and publications it has sponsored, Aurelio Peccei and Alex King travelled literally millions of miles visiting heads of state in practically every country in their efforts to encourage a rational, cooperative approach to a global future. They were persona grata in every capital, whether East or West, North or South. Several meetings of heads of state of more than 20 countries (excluding the super powers) with a few Club of Rome members were held, notably in Salzburg (1974), Guanajuato (1975) and Stockholm (1978). Successive meetings have shown increasing awareness of the problems on the part of the heads of state and, depressingly, increasing pessimism regarding the feasibility of addressing those problems effectively within the constraints of political institutions.

I was privileged to attend the Stockholm meeting with Heads of State, which was held in the Grand Hotel at Saltjebaden near Stockholm. There was lots of excitement – dozens of police cars at the front and a team of men patrolling the perimeter armed with automatic weapons and accompanied by police dogs. The meeting room was sealed and guarded between sessions.

It was agreed that there would be no published record of such meetings but I still have my own extensive notes. Typical of the gist of individual despairing comments are:

“As ministers, we have received a great deal of information, forecasts and the results of analysis. What is lacking is political decision. Most politicians are aware of the nature of the problems, but no decisions are taken. Why? The man in the street is not prepared to make sacrifices and the politician will not fight this attitude – indeed he cannot without risking his political life. Sacrifice is against trade union principles. There are two possible approaches: One is to try to build up an ethic which substitutes satisfaction for material reward. The other is to frighten people to the point where they will make sacrifices in order to avoid catastrophe. Both methods must be attempted...”

and:

“Is it possible to introduce unpopular measures in a democracy? Can the conditions be created for taking actions in the long-term global interest? Has the democratic process first to be blocked?......We must not consider departing from the democratic process, either in principle or in practice – events would snowball in the direction of totalitarianism and who can guarantee that an all-powerful government is good? Rather we should try to convince the public that the less popular measures are essential to the future. We must call for sacrifices in the short term for the benefit of all in the long term...”

and so on. But they were all convinced that their political survival was at stake if they initiated the measures that are essential for global survival. Some ministers might have been prepared to make that sacrifice except for the fact that their probable successors had less knowledge of global problems and were less sympathetic towards solutions than they were, so the situation would not be improved by their resignation. Prime Minister Trudeau is also reported [11] as having said something to this effect at the Salzburg Conference.

11. Looking Back on the Future, by Fred G. Thompson. Futurescan International Inc.

The meeting in Saltjebaden was chaired by the Prime Minister of Sweden. Sam Nilsson, former Secretary of the Nobel Foundation and now Secretary of IFIAS briefed him for the meeting and sat beside him during the sessions. Towards the end of the last session I saw Sam re-entering the room looking very agitated. As he passed me I caught his arm, sensing that something was wrong. The PM had asked Sam to prepare a report on the meeting, but Sam had taken literally the statement that there would be no record, so he had not taken any notes. I handed him 17 pages of notes, minutely written on Hotel notepaper (I still have them in 2005). You would have thought that I had saved his life. It certainly made his day.

Twelve years later, when I attended the 20th Anniversary Meeting of the Club of Rome in Paris in October 1988, many similar things were said. There seems still to have been no progress towards breaking the political impasse which paralyses national and international action against global threats. In the meantime the global predicament intensifies and becomes at once more difficult and more costly to address. I am afraid that it becomes less and less likely that it ever will be faced in time to prevent irreversible chaos and the collapse of civilization.

The Club of Rome changed profoundly after Peccei’s death. Peccei would have no employees, no-one who depended on the Club of Rome in order to make a living. To achieve this he spent a great deal of his own time and money on travelling the world to spread his message and he generally borrowed secretarial help from friendly institutions. In this way the Club could be free from criticism. There was no incentive to keep it going to preserve anyone’s livelihood, nor could it be swayed by the influence of financial supporters. Peccei proudly referred to it as a non-organization.

After Peccei’s death in 1984, Alexander King became the “temporary” President of the Club of Rome. He held many of the same views about the necessity for independence. But there was no longer an independent source of funds and the Club was left in a quandary, whether to maintain its non-organization status or whether to acquire the minimum amount of organization necessary to solicit and administer funding. After a long period of indecision on the part of the Executive Committee, an Executive Secretary was appointed and a small bureaucracy was started. Club members are still divided on the wisdom of this decision, but alternative suggestions are scarce.

The 20th Anniversary of the Club of Rome was held in Paris in October 1988. It was a magnificent affair with sumptuous lunches, receptions and dinners every day hosted by the Government of France and the City of Paris. This was in stark contrast to discussions on the worsening conditions in the third world. The meeting room was equipped with closed-circuit TV so that you could always see a close-up not only of a featured speaker, but of any one of the 80 or so members around the open rectangle of tables who intervened in the discussion. There were also about double that number of observers round the perimeter and the event was fully covered by French TV. I don’t think it made it to North America.

The meeting, which lasted four days, was chaired by Alexander King. Participants included Federico Mayor, Director General of UNESCO, Prince Hassan of Jordan, Cardinal König of Austria, Emil van Lennep, formerly Secretary General of OECD, Julius Nyerere, formerly President of Tanzania and Michael Casadessus, the President of the International Monetary Fund.

In spite of an over-crowded schedule which, one day made everybody arrive nearly two hours late for a reception by the Mayor of Paris (a former Prime Minister of France) at the Hotel de Ville, some of the presentations and discussions were excellent.

It was pointed out that Governments are intrinsically cautious. They study and prevaricate; they like to be absolutely certain before they act. But this is an age of uncertainty. We cannot afford to wait for all the data before starting the treatment of global ills because, while we are waiting, the patient may die. We already have enough scientific basis for action on many global problems including some of the most urgent of them. We only lack the courage to act in spite of vested political and financial interests.

It was, perhaps, the current Prime Minister, Michel Rocard who, in an excellent speech, made the remarks most pertinent to the global predicament. He said:

“.....there are major long-term trends that are well known to us. We know the population growth rates; we know that oil and gas resources are not inexhaustible; we can predict what Europe’s unemployment rate will be in the absence of healthy, enduring growth; we can see that many third world countries are becoming poorer..... We should beware of seeing uncertainty where there is none, because what is uncertain today is the nature of our response. From this, I conclude that we cannot use the fact that we are governing in a situation of uncertainty as an excuse for mere short-term management. On the contrary, it obliges us to seek to master those long-term trends which, if we do not take care, could lead us into wholly undesirable situations. Faced with instability, public opinion demands constancy of its politicians; faced with disorder, it expects to see a certain concern for rationality; faced with complexity, it demands a lucid analysis of the constraints; faced with uncertainty, it calls for sufficient determination to influence the course of events.”

Under the heading “Can Leaders Tell the Truth and Still Remain Leaders?” an American Professor, Donald Michaels, told a few home truths about leadership. He pointed out that we suffer from leaders who are afraid to acknowledge the existence of certain major problems because they are reluctant to admit that they do not know what to do about them. Consequently the problems do not exist in their political sphere. For many years the environmental devastation due to the use of fossil fuels has fallen into this category in North America. It is a sad commentary on our leadership.

In February 1990, Alexander King, at 83 years of age, retired from his position as President of the Club of Rome and settled in London after a serious illness. He was succeeded as President by Ricardo Diez-Hochleitner, President of the Spanish Association for the Club of Rome. The Secretariat in Paris was headed by Bertrand Schneider who, for several years did a remarkable job of holding the Club together. He became the centre of communication and action. Schneider was co-author with Alex King, of the only book ever issued directly by the Council of the Club of Rome, namely The First Global Revolution published by Pantheon in 1991. Otherwise the ’90s lacked the inspiration and evangelic zeal of the earlier periods in the life of the Club. In April 1999, the Paris Secretariat was suddenly abolished. The Head Office of the Club of Rome was moved to accommodation in the UNESCO building in Paris. A “General Manager”, Uwe Möller, located at Hans Rissen in Hamburg, was appointed and the ill-defined responsibility for “co-ordination” was allocated to Hans Unger in Vienna. Bertrand Schneider was caused to resign his membership in the Club.

These changes, which were made without the knowledge or advice of Dr. King, stimulated a good deal of adverse comment and acrimonious exchanges between members and the Executive Council. Alexander King, with the agreement of the President, distributed his own new “Manifesto” to all the members of the Club of Rome, in the hope of clarifying the situation. It was received with little enthusiasm by the new Executive. Alexander King saw no alternative to resigning from the Club of Rome, which he did in 1999 without any apparent recognition by the Executive of his seminal role in the creation of the Club of Rome or of his 30 years of dedicated service to it.

In the year 2001, the new Executive named Prince El Hassan bin Talai as the new President of The Club of Rome. In 2004 the Club still seems to be struggling to recover from the revolutionary changes it suffered at the turn of the Century.

Members have asked each other for several years whether there is any longer a need for a body like Club of Rome. Governments and the public are now becoming more aware of the kinds of global problem described by Peccei and elaborated on in projects that have been sponsored in earlier years by the Club of Rome. In spite of these efforts the political and substantive moves to alleviate the problems are woefully inadequate. The need for a Club of Rome may now be greater than ever.